– Hans Selye, Endocrinologist & founder of stress theory Your body was created with specific response systems in place to ensure that your body and all its systems function optimally so you feel, think, and perform at your best. Feedback loops are meant to maintain a balance (homeostasis) between stress and recovery. The problem begins when these stress systems become overactive or overloaded due to either acute stress (short term) or chronic stress (long term). When our neuroendocrine* systems are out of balance we experience:

chronic fatigue/low energy levels a compromised immune system circadian rhythm is out of whack low levels of creativity and inspiration mood disorders stress disorder anxiety disorders

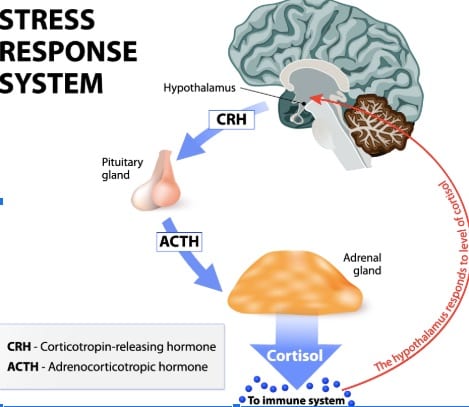

(*neuroendocrine: pertaining to the nervous system and hormonal system) Activation of the HPA axis is a big part of the stress response process. In fact, the primary role of the HPA axis is to regulate the stress response. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis (HPA) is where your central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and hormonal system intersect to create a cascading symphony of signals, feedback, and chemicals in response to any perceived stress or potentially painful situation. This results in the release of stress hormones that then circulate through your bloodstream.

HPA Axis Dysfunction:

The HPA axis plays an important role in helping you deal with the challenges and demands in front of you. In its essence, it’s a self-preservation mechanism to ensure your survival. Under any actual life-or-death threat, such as a fire in your house or a stampede of wild animals coming at you, this system is in place to save your life and so you either fight, freeze, or get the hell out of there. This is your built-in survival program and it gets activated along with your sympathetic nervous system (SNS). If your HPA Axis and SNS were only activated during times of actual imminent danger, you’d see a balance between SNS and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which is what the body is programmed to achieve as we’ve seen. The problem is that our physiological response to stress is the same when it is real life or death, and imagined or perceived. So, if you’re interpreting your boss’s tone to mean you’re in trouble when he calls you into his office, you’ll be anticipating something ‘bad’ to happen (you might think: “Oh my gosh, he’s going to fire me!”) The minute you believe what you’re imagining and anticipating to be true, your body will begin to sound the stress response alarm, which will begin to go off in your brain’s hypothalamus. Naturally, though, if we’re chronically stressed out, anxious, or overwhelmed we very well may be experiencing a chronic imbalance of our HPA Axis and our SNS. This means we have a chronic imbalanced amount of stress hormones in our bodies. This is because we have trained ourselves, (whether we’re consciously aware of it or not), to see an overabundance of potential threats and stressors in our everyday lives. Anxiety keeps us on high alert most of the time and so we keep spinning our wheels and depleting our inner resources. This leads to dysregulation of the stress response, which leads to increased risk factors for other dis-eases such as autoimmune conditions. Stress or trauma experienced in early life also increases the chances of HPA axis dysfunction. This is why it’s so important to learn to manage stress and emotions in daily life – to counter these effects. Adding to our anxious load is the distinction between internal stressors and external stressors. We’re pretty much all familiar with external stressors: insane workloads, juggling personal and work demands, missed flights, fights with family, financial pressures, etc. We’re probably less familiar with internal stressors that also impact our body’s stress response, many times just as much as the external ones. Our body perceives internal stressors even when they’re ‘silent’ and go undetected by us such as when we have a gastrointestinal infection and don’t know it.

HPA Axis Activity – Step by Step:

It’s helpful to understand the general/main sequence of events involved in the HPA axis activation. Three endocrine (hormonal) glands are involved:

- The Hypothalamus (aka: the Master Gland, the Boss)

- The Pituitary gland (does what the Hypothalamus tells it to do)

- The Adrenal glands (they sit atop the kidneys) The HPA axis functions like a domino effect which starts at the first point – the hypothalamus. From there the dominos keep falling and the final destination is the adrenal glands which produce and secrete a type of steroid hormones called glucocorticoids, which include cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone.” #1 – Stressor is perceived (real or imagined, internal or external) ↓ #2 – Internal body alarm sounds ↓ #3 – Hypothalamus (as First Responder) produces signaling molecule CRF (Corticotropin Releasing Factor/ aka: Stress Master Switch) ↓ #4 – CRF signals to the Pituitary gland to release ACTH (Adrenocorticotropic Hormone) ↓ #5 – ACTH travels via the bloodstream down to the Adrenal Glands ↓ #6 – The adrenal cortex secretes corticosterone, cortisol, epinephrine, & norepinephrine (noradrenaline) ↓ #7 – Once the Hypothalamus senses high Cortisol levels, the Stress Response is shut off (Negative Feedback Mechanism)

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF): The Stress Master Switch:

CRF, the Stress Master Switch, can affect every organ and cell in your body when any stressor (real or imagined, internal or external) is perceived. It’s also known as CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone). Dr. Yvette Tache has conducted groundbreaking research on the role of CRF in stress-related alterations of the Gut-Brain Axis. Her work is exceptionally important because it’s showing how gut dysfunctions like IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) and IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) may be stress-related:

Though CRF at low doses stimulates memory and learning, higher doses have an opposite effect and also increases anxious behavior. (1) High CRF levels can increase sensitivity to gut signals, which can be experienced as abdominal pain. (2) CRF acts in the brain stress network to increase colon secretions of water and mucus and muscle contractions. (3) These muscle contractions and CRF related bodily reactions “lead to the development of watery stool/diarrhea, and increased permeability within the lining of the bowel. (The more permeable the bowel lining, the easier it is for substances to pass through, which could allow the passage of bacteria within the intestine into the bowel wall.)” (3) CRF related stress-induced gut reactions also impact the makeup and activity of our Microbiomes. (2) The amygdala contains CRF expressing neurons. Spiking CRF levels in the amygdala result in anxiety-like behavior (4) In The Mind-Gut Connection, Dr. Emeran Mayer discusses one of his cases studies – a patient with cyclical vomiting syndrome: “Patients with this disorder may be completely symptom-free for several months or even years, even though their CRF system is primed all the time. But when they experience additional stress, a recurrence of symptoms is triggered.” (2)

Cortisol: The Stress Hormone

When balanced in the body Cortisol, the main stress hormone can be beneficial and we need it to function properly. Our own body’s rhythm is programmed to have levels of cortisol rise around 6 am, peak at around 9 am and go down again until around 12 noon. (5) Thanks to the release of cortisol we have the energy to wake up every morning. We are alert and aware of our environment. Balanced Cortisol release levels can help mobilize energy in the body by controlling blood sugar, regulate metabolism, help reduce inflammation, and it also helps pregnant women by supporting the fetus during gestation. (6) When imbalanced – meaning when there is a prolonged dramatic increase in cortisol response due to chronic anxiety and stress, our health deteriorates and our immunity is comprised. REFERENCES : (1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3169435/ (2) Emeran Mayer, MD, The Mind-Gut Connection, 2016 (3) https://iffgd.org/research-awards/2005-award-recipients/report-from-yvette-tache-phd-stress-and-irritable-bowel-syndrome-unraveling-the-code.html (4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8971127 (5) Chek, Paul, How to Eat, Move, & Be Healthy, 2004 (6) http://www.hormone.org/hormones-and-health/what-do-hormones-do/cortisol