When it comes to cinema, the director is involved in every creative decision that affects the film—the tone, the cast, the production, the editing, among others. So, what happens when a director dips? A lot of times, the film is simply canned altogether. For high-profile projects, another director might be brought on to finish the project. That, of course, can spell disaster as ideas between the former director and new director clash and result in a disjointed experience. However, here are several movies where directors changed partway through development yet the final film still ended up being successful.

10. Bohemian Rhapsody (2018)

Bryan Singer—the man behind X-Men (2000) and The Usual Suspects (1995)—was initially billed to direct the Freddie Mercury biopic, but then 20th Century Fox fired him for barely ever being on set. A bit inconvenient considering he was in charge of, like, everything. Lead actor Rami Malek suggested Dexter Fletcher to replace him, feeling that he would probably “do a better job.” And given that Fletcher actually turned up and completed the film to much public success, Malek was probably right to say that. Fun fact: Dexter Fletcher was also making another similar, glittery musician biopic at the time in Rocketman (2019)!

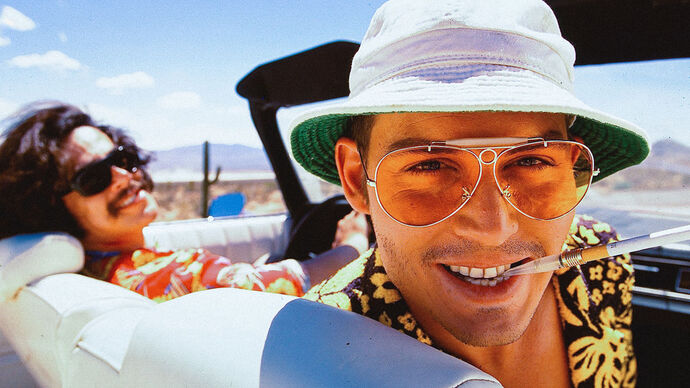

9. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998)

Terry Gilliam is one of the zanier film directors, which made him the perfect match for a film as wild as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Everything about this road movie is cranked up to a hundred, with its protagonists pumped up with every kind of drug imaginable as they cry to the voice of Grace Slick in the bathtub. Rhino Films had been begging Terry Gilliam to direct the project for nearly a decade to no avail, so they settled on a different director: Alex Cox. But then Cox left production over “creative differences.” Fortunately, upon re-reading Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, Terry Gilliam realized he actually loved the story and agreed to step in. Although it wasn’t a success at the box office, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas has become a massive cult favorite thanks to Gilliam’s direction, who upped the budget and let the “bats out” (as Cox put it).

8. Ratatouille (2007)

Jan Pinkava began working on Ratatouille in 2007 in the hopes it would become his feature directorial debut. Pinkava was the mind behind the character of the cooking rat, but the project eventually stalled and Brad Bird was asked to take over as director. Though the general plot remained the same, Pinkava’s self-proclaimed “European sensibility” was lost under Brad Bird’s direction. (Jan Pinkava still nabbed a co-director credit, though.) Although you wouldn’t think so from Ratatouille’s success as a Pixar fan favorite, the studio had little confidence in the movie, which took seven vulnerable years to make—and Brad Bird only showed up 18 months before the film’s eventual release.

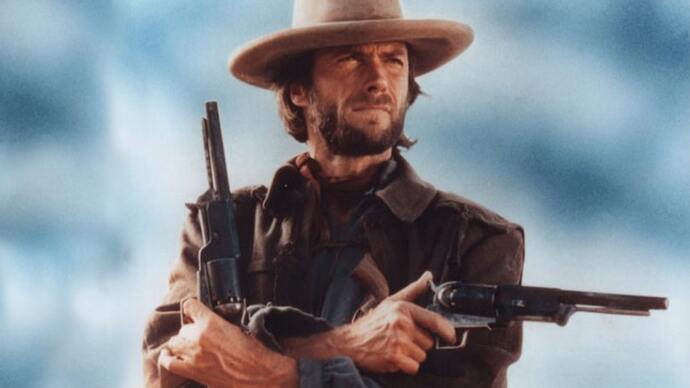

7. The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

Have you heard of the “Eastwood Rule”? It’s a rule that prohibits someone from firing a director and then taking over their role—and that rule ws passed because of The Outlaw Josey Wales. The Outlaw Josey Wales was initially directed by Philip Kaufman, with Clint Eastwood headlining as the eponymous character. Eastwood pressured the studio to fire Kaufman, which they did, and Eastwood himself ended up behind the camera in his role. Why the push to fire Kaufman? Apparently, there wasn’t much substance to it; they’d simply asked out the same woman. Despite the roaring success of The Outlaw Josey Wales, most of the team felt that Kaufman unjustly lost credit for all the work he put in. It was such an issue that The Director’s Guild of America decided to ban Clint Eastwood’s sneaky move from ever happening again.

6. Brave (2012)

Brave earns a spot on this list because, even though Pixar controversially shifted gears through production, it’s ultimately praised as a revisionist fairy tale that successfully blends modern values with ye olde fantasy. But why was Brave controversial? Well, Brenda Chapman was set to be the first female director of a Pixar feature, after she’d slowly worked her way up the Disney company ranks for decades. But then she ended up getting booted and replaced by male director Mark Andrews. Originally called The Bear and the Bow, Chapman was inspired by the relationship she had with her own daughter when conceptualizing Brave. Six years into the project, Chapman was removed from the team and replaced by a director with considerably less experience. We’re still struggling to find a good reason why.

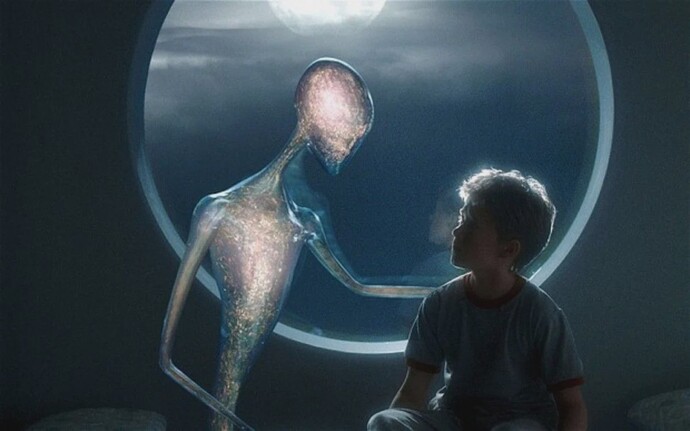

5. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick are two of the biggest names in the film industry, and they were both named director of A.I. Artificial Intelligence at different points in the project. Stanley Kubrick was the first to be tasked with bringing Brian Aldiss’s 1969 novel Supertoys Last All Summer Long to life. He acquired the rights and set a team of writers working on the script for an arduous two decades before it was all handed over to Steven Spielberg. During the 1980s, Kubrick felt that CGI technology wasn’t advanced enough to make a film starring a robot boy and he had no faith in child actors. Spielberg, on the other hand, showed us time and again that kids have big-screen potential. This time, he perfectly cast Haley Joel Osment for the role. And while production remained stagnant for a while, Kubrick’s death in 1999 spurred Spielberg to finish the Oscar-nominated sci-fi classic.

4. Jaws (1975)

A.I. Artificial Intelligence wasn’t the first time Spielberg came in to replace a director. The lesser-known Dick Richards was actually the first director in charge of Jaws, which might surprise you given that Jaws is the film that launched Spielberg to Hollywood stardom. For starters, Richards kept calling the infamous Great White Shark a “whale” during preproduction, either as a genuine mistake or some weird kind of irony. This red flag, combined with his other reportedly annoying habits, got him kicked off the movie. The fact that Jaws went on to shape the American film industry in such a huge way under Spielberg means it was probably a good decision.

3. Spartacus (1960)

Directing a film as epic as Spartacus—with its prestigious cast, huge budget, and massive ancient sets—takes guts and determination. Even directing a small movie is no easy feat, but a film like Spartacus is enough to intimidate even the greatest directors. Except for maybe Stanley Kubrick, who lived for the challenge! The historical drama was originally given to Anthony Mann, who—despite his victories in the Western genre—was too nervy for the job. Producer and star Kirk Douglas fired Mann and put Kubrick in charge of the slave revolt.

2. Gone With the Wind (1939)

Gone With the Wind had a hell of a time getting made, in every type of way. Not only was it a story of epic proportions, adapted from Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 book, but it took years to secure the cast and went through not two but three directors! The first was George Cukor, who’d been prepping for two years and insisted on meticulous—and expensive—period detail. He was fired from the set 18 days after filming commenced. (Rumor has it that his open homosexuality played a dark role in his removal.) Next was Victor Fleming, who was already directing the ambitious MGM film The Wizard of Oz when he was brought in. Fleming took a break from the project after a nervous breakdown (that many suspected as fake). Director Sam Wood stood in for Fleming until his return. Once you understand the kind of chaos that happened during the production of The Wizard of Oz, a breakdown is understandable.

1. The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Up until The Wizard of Oz, audiences were used to only seeing black-and-white films. The movie teases us with opening scenes in sepia, but once Dorothy lands in the magical land of Oz, everything turns Technicolor. The technical side of all this was exhausting, as was the rest of production: uncomfortable costumes, 16-hour shifts, extreme diets, pills, and, of course, four different directors. Alongside Victor Fleming was George Cukor, who switched between The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind like a tennis ball. (Did MGM have no other directors?) There was also Richard Thorpe and King Vidor, who both helped direct. In the end, Victor Fleming took credit for both movies.